PHOENIX – David Hondula recently got a job he never dreamed of – maybe because it never existed before. He’s the director of the city’s Office of Heat Response & Mitigation, which is touted as the first publicly funded municipal office of its kind.

Hondula, who comes to city government from the Arizona State University School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, realizes the “monumental task” he faces during a time of severe drought and rising heat, but he looks forward to the challenge.

“It’s an exciting time to be moving into this role,” said Hondula, who once questioned whether there was anything worth studying about heat.

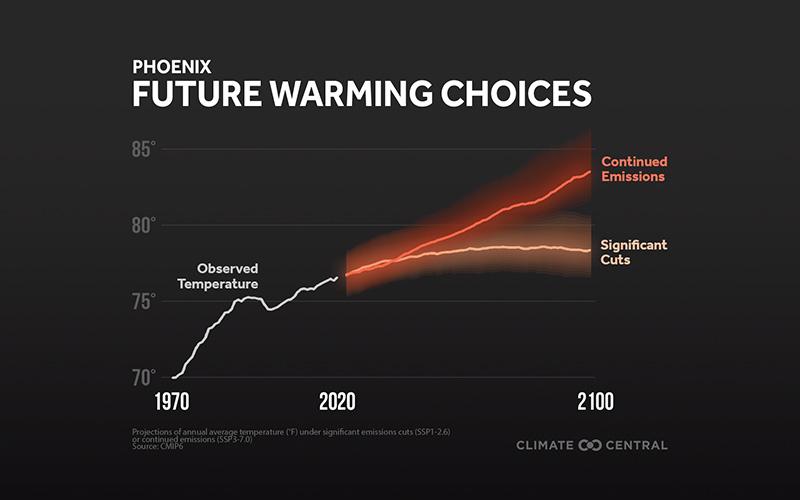

The Office of Heat Response & Mitigation was officially announced Sept. 14. Phoenix is one of the fastest warming cities in the country, according to a Climate Central report based on government data, and in June, the metro area endured a record six consecutive days of temperatures over 115 degrees. Globally, July was the hottest month on record, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“We are kicking off a city wide approach to addressing the heat,” Mayor Kate Gallego said on Oct. 4. “We hope to improve the way we build buildings, we hope to plant more trees, we hope to save more lives of those who are most vulnerable in our community. We know that heat has to be at the forefront as a desert city, and Phoenix wants to lead the way in finding solutions to making our city safer and more sustainable.”

Heat doesn’t operate with the captivating visuals of tornadoes, it does not attack with the immensity and ferocity of hurricanes, nor does it turn cities into scenes from disaster movies filled with floods and earthquakes. But heat is the number one weather-related killer in the U.S. killing an average of 138 people a year from 1990 to 2019, according to NOAA. In 2020, heat killed 313 people in Arizona alone, state data show.

Phoenix has committed to stopping that trend.

“This is not a temporary commitment. We’re remaking Phoenix government with this (office),” Gallego said.

The City Council in May approved a budget that included $2.8 million focused on climate change and heat readiness, which included this office. Gallego said Hondula’s team will collaborate with other city departments, such as Parks and Recreation and Street Transportation – which already have programs to address rising temperatures.

The new office will have a staff of four, and has two project manager positions yet to fill. One will focus on increasing the tree canopy throughout Phoenix. The goal is to reach 25% tree canopy cover in the city by 2030. The other will focus on built infrastructure – increasing shade structures and developing ways to cool structures and streets, particularly at night.

David Hondula’s “monumental task” as the first director of the city’s new Office of Heat Response & Mitigation will be battling extreme heat – the number one weather related killer in the U.S. – in one of the sunniest cities in the world. (Photo by Kevin Hurley/Cronkite News)

The general

“I worked in our geography and planning program for the past decade with almost an exclusive focus on heat,” Hondula said of his eight years with ASU. He will maintain a part time position with the university but will be employed full time as the director of the Office of Heat Response & Mitigation.

Hondula said his decision to leave academia hinged on the opportunity to have a community impact.

“In the academic community, we are terrific at studying the problem, talking about solutions to the problem, imagining what it might look like to solve the problem, I’m excited about the chance to solve the problem,” he said.

Gallego said she’s excited to work with someone who “makes the data case for why these investments make sense,” and will make sure taxpayer dollars are effectively used to address climate change.

“He is going to be able to take us to the next level, so that when there’s an exciting new solution, its coming from Phoenix,” Gallego said.

Jersey boy heads west

Hondula was born and raised in New Jersey, about 25 miles inland from the Atlantic shore, and says his interest in weather started before he could remember. Hurricane Floyd came through New Jersey in 1999 when he was 14.

“I very specifically remember being out with my parents VHS camcorder trying to document how fast the water was flowing in the flooded creek near where we lived,” he said.

He followed his interest at Bridgewater-Raritan High School in Somerset County, where he served as one of their “on-air TV meteorologists,” doing a few broadcasts a week for the school. One memorable recurring segment of the show was inspired by “JayWalking” with Jay Leno, where Hondula and his classmates would ask strangers weather questions on camera.

Hondula went on to earn his Ph.D. in environmental sciences from the University of Virginia in 2013 – but he never had a specific interest in heat.

“I didn’t even know there was anything interesting to study about heat,” he recalled.

Hondula expected his research would focus on generating better forecast models to understand when lightning was about to strike.

“Unfortunately my skills in electricity and magnetism were not as strong as they might have needed to be,” he said.

His Ph.D. adviser, Bob Davis, was in a field Hondula knew little about called biometeorology, which studies how weather impacts humans. Davis’ papers on heat piqued Hondula’s interest.

“All the sudden, one thing led to another and there was a wealth of unanswered questions out there to pursue from a research perspective,” he said. “That really grabbed me intellectually.”

Arizona, a place he visited at a young age and “always had a fondness for,” was the perfect landing spot. To this day, he prefers the hottest Arizona day to the “hottest and muggiest day” in Virginia.

He joined Arizona State University as a postdoctoral researcher in 2013; he said it was a perfect match because of ASU’s “world leading” research in urban climatology.

“A chance to go to that institution and have the surrounding environment be ideal for understanding various aspects of this problem, it seemed too good to be true,” Hondula said.

Now, his expertise has taken him from observation and analysis to the front lines of climate change – a position that was never part of his “plan, vision or dream.”

“These types of positions didn’t even exist,” he said of his new job. Even as recently as this spring, as he and his colleagues advanced the conversations toward “heat governance,” Hondula said the idea of any of them serving a role in local government “never even bubbled up in conversation.”

“Someone might have said it in passing… as a joke,” he added.

Hondula said it took him a while to even consider applying to direct the heat office because he enjoys his work at ASU.

“As an academic researcher, our dream is always to have some meaningful, tangible societal impact,” he said. The dream had been realized, this was his chance.

(Graphic courtesy of Climate Central)

The new front

You can count on one hand the number of comparable “heat offices” around the world. In April, Miami-Dade County announced that Jane Gilbert would be its interim chief heat officer – the first in the U.S. This position is funded by the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance – which aims to reduce extreme heat risk for the most vulnerable populations.

Gilbert, who previously served as Miami-Dade’s resilience officer addressing climate change and emergency response, said the heat governance discussion in Miami was brought on by other weather disasters.

“After Hurricane Erma in 2017, we lost 12 people in the county north of us at a nursing home because of the widespread, extended power outage,” she said. Florida law now requires assisted living facilities to have backup generators to provide air-conditioning during power outages.

Miami is at high risk for rising sea levels and hurricanes, Gilbert said, but in canvasses of community members, heat concerns came up the most, especially in socioeconomically vulnerable areas.

Like Phoenix, the Miami office aims to protect people who are most at risk.

“All of these increasing shocks and stresses related to climate change impact our most vulnerable first and most,” she said. “So the solutions need to have an equity lens.”

Miami-Dade, Athens, Greece and Freetown, Sierra Leone, are the only places with city officials in charge of managing heat, but all are funded by the EHRA.

Hondula runs the first publicly funded heat response office in Phoenix, where temperatures continue to set records. In 2020, Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport reported a record 53 days above 110 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services .

“Here in Maricopa County,” Hondula said, “we have an air quality department, we have a flood control district, who’s been in charge of heat is the question we found ourselves asking.”

Hondula’s battlefield is one of the hottest cities in the country in a global fight against climate change. But he believes that every heat-related death is preventable.

“I think the measure of success for the office, although it is challenging, is to see those numbers come down,” he said.

Increasing tree cover will be one of the primary focuses for his office. The development and expansion of programs like cool pavement will also be used to reduce the urban heat island effect – when built environments absorb heat and reemit it, causing rising temperatures in the city.

Hondula believes that every office in city government has a role to play, and he expects to be heavily armed with strategies.

“It’s been really impressive and encouraging in my first 14 days getting to meet people at different departments, meeting city council – there are a lot of ideas in this building already,” Hondula said. “I’m not sure I’ve had a conversation yet where somebody hasn’t had an idea.”

For Gallego, this office is another step in her progressive approach to climate change.

“For me, this has been a career wide challenge,” she said. “It’s key to Phoenix that we lead on issues of climate and sustainability. I want it to be part of what we’re known for.”

Now a community under siege from rising temperatures has an ally in the city government. And Hondula sees community engagement as an integral part of the office’s success.

“Heat will be part of the future success story of Phoenix as a booming and growing city, and the chance to be part of that is really special,” he said.